(Report for the MP of Bokora County Karamojaland, Hon Achia Terence. By Simon Bird and Alex Brigers.)

“I really want to see the Queen of England arrive, but fear I will be arrested if I go to the streets during CHOGM !” says Frances, a Karamojong from Kakajjo-zone in Kampala.

Her Majesty The Queen and The Duke of Edinburgh are scheduled to visit Uganda this month to open the Common Wealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) on the 23rd to 25th of November 2007.

The President of Uganda, Mr Museveni has been desperately trying to clean up the city before Her Majesty and some 5,000 delegates from 53 countries arrive. Some say it is a superficial clean-up: miles of grass has been planted on road sides; thousands of pot holes filled; litter bins distributed; and, now, the Government is trying to remove beggars, and others that they regard as ‘undesirable’, from the street, 90 percent of which are Karamojong.

KARAMOJA WOMEN on the street:

“We are not ready for CHOGM,” say these Karamoja women, who fled their homeland because of famine and conflict. “The city council are rounding us up and returning us to Karamojaland where we have nothing.”

When I first arrived in Uganda, 6 months ago, the Karamojong could be seen everywhere in Kampala, sweeping fallen beans, maize, or anything edible up from the ground. In the centre of town they would leave babies alone on the pavement to get money. These people were the exotic invaders of the city, sporting tribal facial scars and an attitude of indifference towards their squalid life in the street and the ghettos.

During my stay, I ran craft projects with some of the Karamojong to help start small businesses. This allowed me to follow their story both in the city and in remote Karamojaland. The interactive paintings I include were made on location to help address some of the issues involved in their way of life.

Inter-tribal conflict in Karamojaland

Overshadowed by the war in Northern Uganda with the LRA (Lord’s Resistance Army), Karamojaland has been virtually unknown to the West. It is a place where education is only just being accepted, and the old tribal culture of cattle raiding has turned sour with the arrival of firearms.

MAP: Karamojaland is a wild, semi-arid desert region covering an area of more than 24,000 sq. miles, bordered by Kenya in the East and Sudan in the North.

For the past 30 years it has been the scene of an inter-tribal conflict over the ownership of cattle and for revenging previous attacks. No full record of casualties exists – successive Ugandan governments have turned a blind eye to the troubles. In 2001, a voluntary disarmament programme was started by the Ugandan Peoples Defence Force (UPDF). This was then upgraded, in 2003, to a forced disarmament programme.

“Over 10,000 guns have been collected since the disarmament exercise started in 2001. It is estimated that some 40,000 illegal weapons are still scattered in the region,” says a UN report on May 22nd 2007.

One of the problems of this disarmament today is neighbouring Karamoja tribes coming to attack villages that have already been disarmed.

“They are coming to take cattle and food stocks, and are killing people, leaving those who most want peace with nothing,” says Daniel, a Local Councillor of Matany sub-County, Karamojaland.

The new radical disarmament method, whereby villages are surrounded and systematically searched, has also been creating extra civilian casualties.

A 2007 report from St. Kizito Hospital in Matany states:

“Over the last three months, there has been an average of 1 victim every 12 -18 hours. Given the fact that those who reach hospital are only the survivors; the actual field mortality must be incredible and of great concern.”

Coupled with this armed insecurity, Karamojaland also suffers from yearly drought. “At least 40 percent of the population lacks adequate, if any, food stocks. The World Food Programme (WFP) will be providing assistance to 500,000 Karamojong during the coming year,” says a report from the WFP, January 2007.

Karamojong in Kampala

I am in Kakajjo-zone ghetto just a stone’s throw from the city centre of Kampala. The ground is muddy and black. I jump a raw sewerage channel to arrive at an open space where women are drying beans and cassava they had swept from the street that morning. At times, there are up to 900 Karamojong staying here. Now, on the lead-up to CHOGM, that number has fallen to about 200.

PHOTO: Kakajjo-zone ghetto.

“Yesterday, the city council surrounded 20 children on the street,” says Frances, who has been in the ghetto 4 years, and is now the acting chief. “They have been taken away.”

He takes me to one of the mothers washing a baby in a dirty bowl next to the sewerage channel. “They would not tell us where they were being taken,” says Maria, 42. “I can only go back to Kampala road to ask again.”

Maria fled Karamojaland because her husband and 1 child were killed during a cattle raid. She took 3 of her 5 children to Kampala leaving the other 2 behind with an aunt.

She does not want to return.

In a drinking room I sit with some Karamoja men, and suck millet beer through a long, wooden straw.

“Are we not Ugandan citizens? Why cannot we stay to see the Queen,” says John, a determined 24-year-old Karamojong, who is surviving by making rat traps out of scrap metal. “We hear on the street and the radio that they want all the Karamojong to leave before CHOGM. Maybe I will leave for outside Kampala, then return after 2 weeks.”

The phenomenon of the Karamojong coming to the city started 5 or 6 years ago with the beginning of the disarmament process. Periodically, the Government removes them back to Karamojaland, but within a few months they have all returned again.

After being re-directed half a dozen times, I finally track down the city council public relations officer responsible for picking up street people.

He welcomes me in with a big smile, as everybody does to a Muzungo (‘white man’). “It is our policy to remove those Karamojong from the street, and to put them into school, and relocate them in Karamojaland. We do not want to encourage more to come to the city. It is there we want to develop them, and deal with the problems from the source.”

I explain that mothers were being separated from their children. He replies, “It is the nature of their begging to send children by themselves to the street. It is not good, or safe, for the children. We are trying to tell them that.”

The children are often taken to Caprinza, an education facility 20 miles from Kampala. Mothers sometimes go there to collect their children, but they have to save up enough money through begging in order to buy them back.

Maria Lokwea was one such case. She says there were a lot of people sleeping together, but she did go to school. Her mother paid 40,000 Ush to take her out. Now, she is back on the street with her older brother’s children.

Next to the old British railway line is another ghetto called Katwe where 80 Karamoja live in a large mud house. Conditions seem slightly better than at Kakajjo-zone. Rent is also cheaper. Fires are going on the mud, and people are cooking chicken intestines and rotten tomatoes they had scavenged from the market.

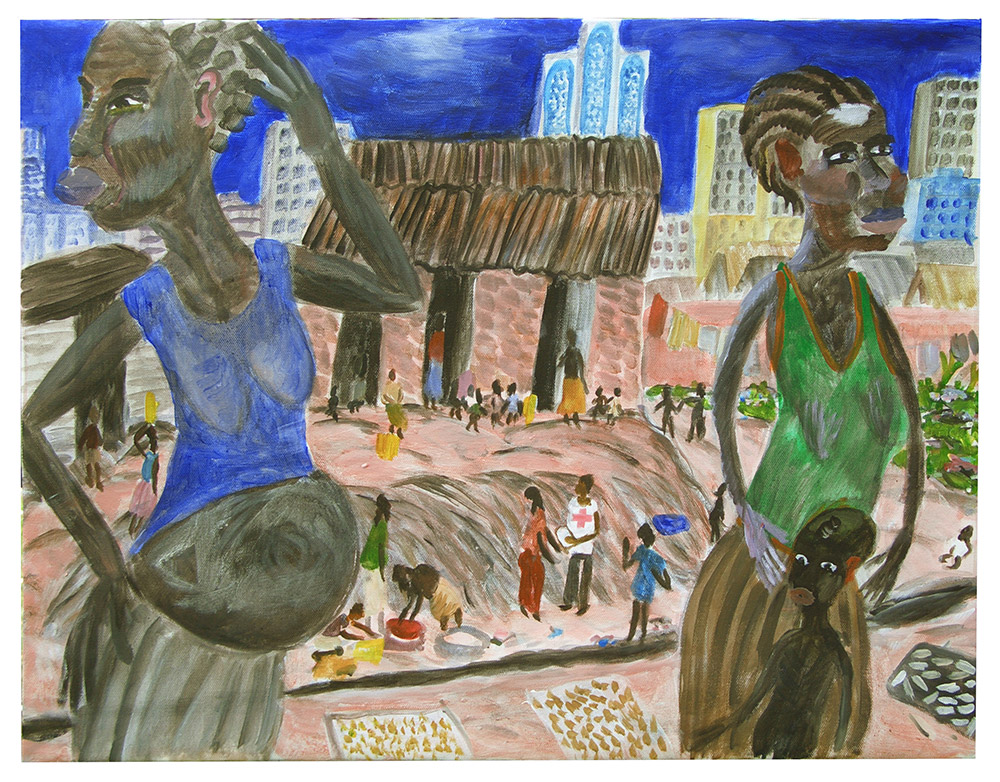

PICTURE AT KATWE GHETTO: I let the Karamojong tell me what they think should be included on the painting; the Red Cross man coming to check on hygiene, and Agnes the pregnant woman.

“I will be having my baby with Helen,” says Agnes, the lady I was painting in the picture. She leads me to a clinic 50 yards away. It is a small concrete hut with a corrugated iron roof.

“I treat some of the Karamojong for free,” says Helen, a registered nurse with a warm smile and large, frizzy hair. “It is not because I feel sorry for them, but because my clinic is just here, nearby. One woman came to Kampala by clinging onto the underneath of a bus. She arrived coughing and with skin diseases, and 4 months pregnant. I delivered the baby, and it is now fine.”

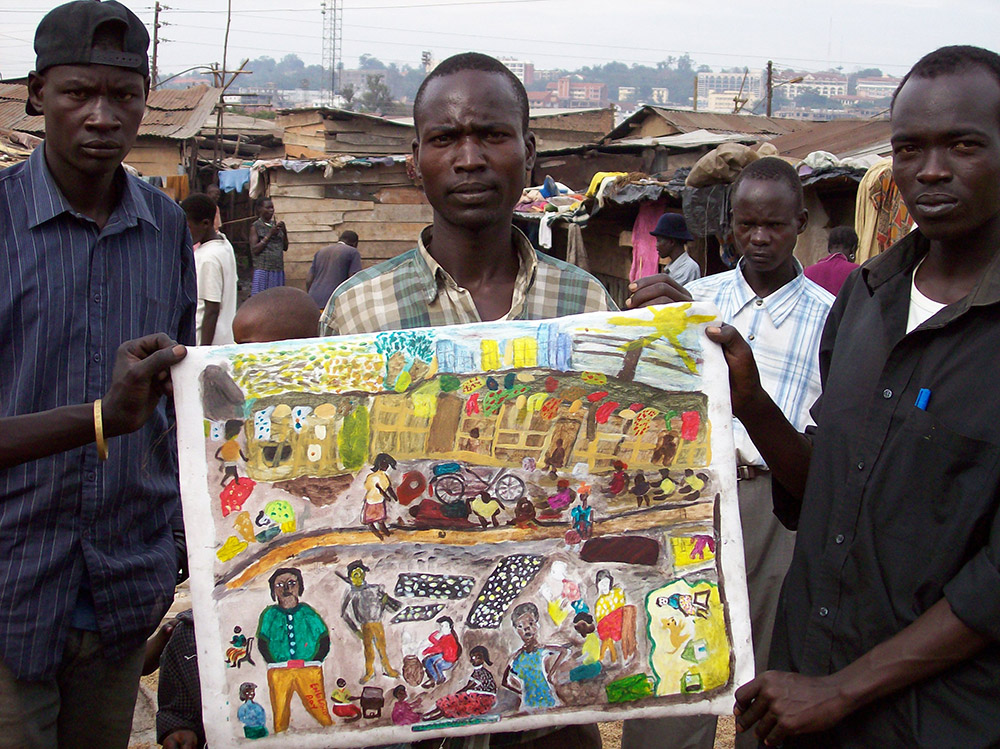

PHOTO: Painting in Kakajjo-zone.

During another afternoon, I organise a interactive painting with 3 people from the ghetto: John (centre), Mr. Lokai (right) and Rooney (left).

John tells me he left Karamojaland because of hunger, but Rooney says it was because he had stolen 10 chickens, and that the family will never forget.

“There are some bad people here as well,” explains Mr. Lokai.

“They have fled Karamojaland not because they are victims, but because they have killed, and fear being revenged.”

They all laugh.

Almost 90 percent of the Karamojong we spoke to in Kampala originate from the central region of Karamojaland. Over 50 percent of which were from one particular sub-county: that of Lokopo.

I feel compelled to visit Karamojaland now to see the conditions myself, and to find out why people are leaving from just one area. Mr. Lokia volunteered to act as translator

Karamoja culture

Karamoja culture

Karamojong literally means ‘the tired old man’. They migrated over 1,000 years ago from Ethiopia, and when they reached what is now Uganda the tired old men of the group said they could go no further. The relatives of the Karamojong can be found all across East Africa: Toposa people (Sudan), Turkana people (Kenya) and the Maasai people (Tanzania).

Karamoja people are the only semi-nomadic group in Uganda. Men live for extended periods with the cattle, moving according to the availability of pasture, and to avoid raiding from the neighbours.

Women and families tend to remain in permanent settlements. These villages may comprise of 10 or more families, who have chosen to live together for reasons of security and support.

The multicoloured waist beads that are worn by the women symbolize beauty; the more beads, the more desirable for marrying they become. Old men often sell off their best cattle in order to buy jewellery for their daughters, so they can fetch a higher bride price. Buying a bride can cost anything from 10 to 80 cattle and goats.

Entering Karamojaland

During the bumpy, 12-hour bus journey, the land slowly becomes drier and more parched. By the time we cross into Karamojaland, the bus is jammed full of men, women, babies, sacks, baskets and chickens.

At the first stop, hordes of skinny kids come running up chanting, “Da ka do do, da ka do do…”

“They are saying ‘give squashy bottles’. Even to me it sounds funny,” says Mr. Lokai with a smile on his face.

PHOTO: View from bus entering Karamojaland.

We arrive in the small town of Matany at nightfall. I see drunken warriors staggering about with little more than a blanket wrapped around themselves. Finally out of the bus, we walk briskly to the house of the sub-county chief, Mr. Daniel Corbie.

“While it is safe during the day, the second it gets dark you should be inside,” says Daniel. “There is still a general insecurity because some people have not given up their guns.”

The next day we meet a student called Basil who offers to guide us to Lokopo.

“Matany is a rich town compared with Lokopo; we have an Italian Catholic church and a hospital. The people from Lokopo have to walk for 2 hours so they can trade here,” says Basil.

I speak to a woman from Lokopo, who is selling bundles of wood in the market area. “I get up early when it is dark to collect wood from the bush. One day we saw men with guns, so we just ran. None of us were shot, but some people

are killed.”

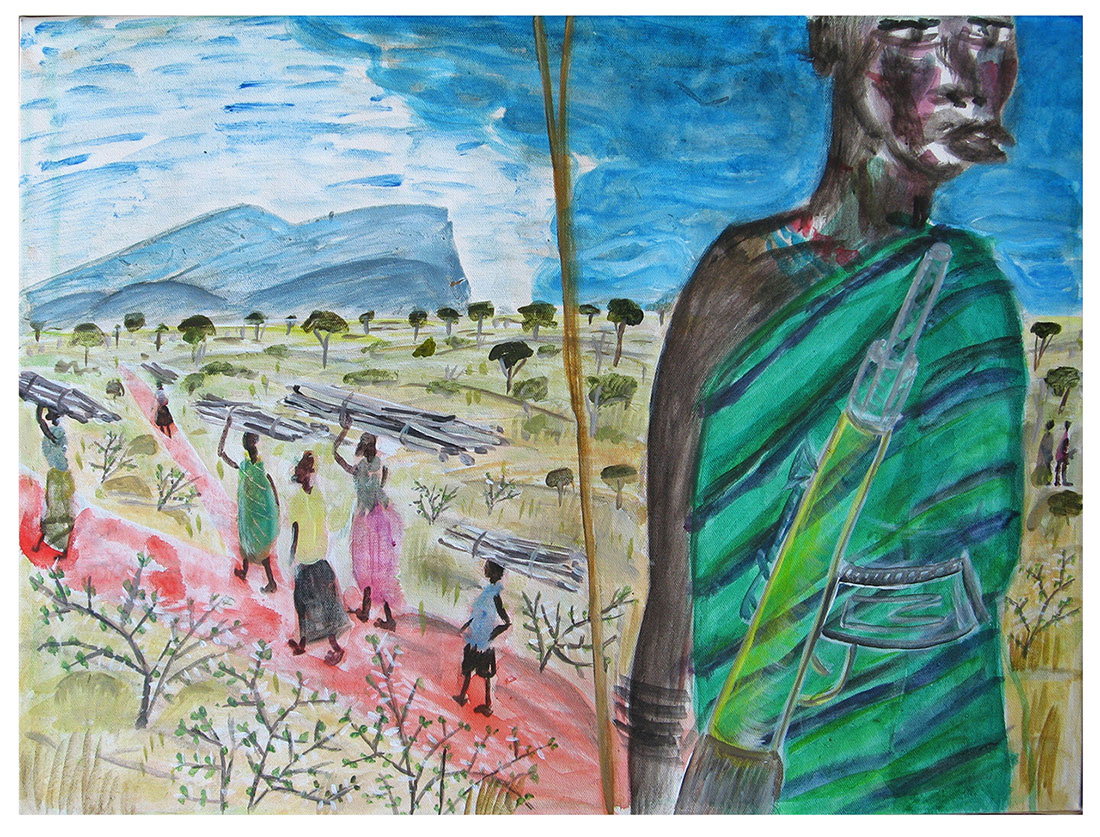

PHOTO: Women selling firewood

Basil tells us that sometimes it is not just raiders from outside that come to take cattle, but those people from within. The cattle, however, are now guarded by the army in the barracks. So, the raiders feel frustrated, and, sometimes, vent their anger by killing innocent women and children in the bush.

PAINTING: Showing women collecting firewood and warrior wearing traditional

blanket. You cannot tell if a warrior is concealing a gun or not.

Walk to Lokopo

It is a 2-hour walk to Lokopo. The countryside is flat and the sun very hot. Acacia trees and thorny bushes are scattered on the plain as far as the eye can see. People walking the other way stop and greet me with hands together.

“They think you are another Italian priest from the church,” says Basil, humorously.

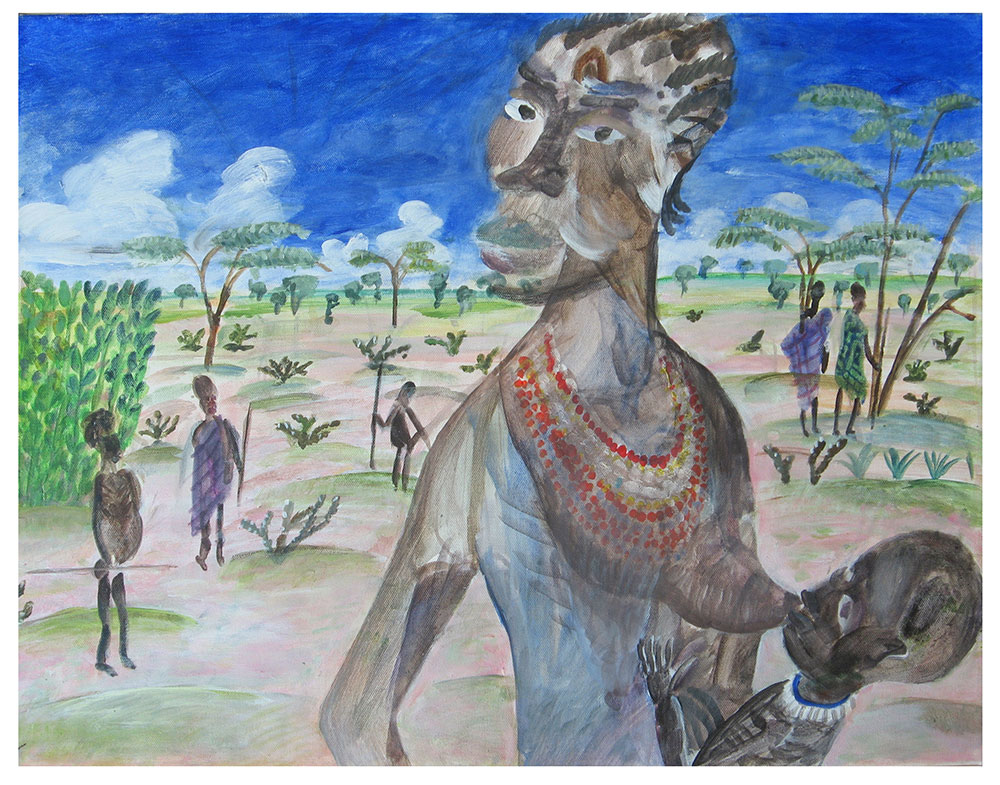

It is an indescribable feeling to be seeing the Karamojong in their homeland and not in the city ghetto. They are tall people with elaborate jewellery and colourful blankets that fit so well into the environment here.

Basil directs us on a short cut to another path. On the way he discovers some bones half buried in the sandy soil. “Someone was killed here,” he says, holding up one of the bones to his leg where it would have belonged.

Basil directs us on a short cut to another path. On the way he discovers some bones half buried in the sandy soil. “Someone was killed here,” he says, holding up one of the bones to his leg where it would have belonged.

“The dead are not buried but left or dragged to the bush to prevent disease. Mothers cry for 20 minutes, then call it a day and get on with their lives. Sometimes they even smear the bodies with sheep fat so animals eat it faster. Death is a part of our culture,” says Mr. Lokai.

Lokopo is made up of about 20 villages, and situated in the middle is a small trading centre.

Every village in Karamojaland is surrounded by a barricade of woven sticks and spiny branches. There is a small entrance which you have to climb through on all fours. At night, these entrances are blocked with extra spiky sticks.

It really makes me realise that these people have lived with inter-tribal warfare for a long time. Giving up the gun must be a difficult thing to do.

In the small trading centre little is going on; some women selling stacks of wood, some selling water, and some men selling black, charcoal-cooked rats from the bush. I buy one of the rats. It tastes like burnt roast pheasant, but with rounder bones – actually, not bad!

Mr. Lokai spots a woman who he recognises from the Kakajjo-zone ghetto in Kampala.

Mr. Lokai spots a woman who he recognises from the Kakajjo-zone ghetto in Kampala.

She is pregnant. “I have returned to have my first baby, and when I am better, and have some money for the bus, I will return to Kampala, because there is too much hunger here,” she says.

We ask if she will use her baby for begging on the street.

“No,” she replies.

Mr. Lokai whispers, “I think I will see that baby on the street very soon.”

PHOTO: Countryside around Lokopo

PAINTING: Showing women and children, who are often the innocent victims of conflict.

A Karamoja elder tells us that a few days before there was a raid on his village on the northern edge of Lokopo sub-county.

Before entering the village, I am alarmed to see several warriors carrying badly concealed AK47 rifles under their blankets.

Mr. Lokai instructs me, not to say anything about it and not to worry. I feel uneasy because this area was supposed to have been disarmed.

We are invited into the chief’s hut, and sit on cow hides; I am offered a bucket of sorghum beer.

“We have been attacked several times in the last few months. It is the Jia in the North; they have taken goats and cows,” says the village chief.

“There is no community here anymore; most people have fled to Kampala, Jinga or Umbale.” He points to a set of abandoned round huts opposite.

I ask what should be done.

“The Government should put more army around the villages to protect us while disarmament is going on. There are just 2 soldiers for the whole of Lokopo; the rest are in the barracks with the cattle.”

The chief goes on to explain that three quarters of the cattle have been taken, along with most of the food that was stored.

Outside, I ask the elder if he ever went on cattle raids when he was younger.

“Yes,” he replies, and gives a laugh. “On one raid we took many cows. There were 100 of us. It was a big battle, but we managed to win.”

I ask if he killed anyone.

He says, “No-one from the village; just those that followed us.”

PHOTO: Lokopo villagers.

On the way back to Matany, Basil tells me that even though this village has guns, he found out that they do not have bullets. The army is checking all roads, so it is difficult to get ammunition. But, in the north of Karamojaland it is easy to get guns and ammunition from across the border in Sudan.

Matany Hospital

Back in Matany, I greet the hospital administrator in Spanish, because I was told by a nurse he was Argentinean.

He gives us permission to speak to some of the patients. “You can be a doctor this afternoon,” he says, handing me a white overall, “so you don’t worry the patients.”

I tell him that earlier in the week I had also been an Italian priest.

There are 2 rooms dedicated to male gun shot victims. Each room has 12 beds, and all are taken.

“I was shot in Lorikitai, a village in Lokopo district. I was sleeping inside the village when I heard the neighbours were being attacked at night by cattle raiders. I went to help,” says Mr Loibar, 30.

He begins to lift the bandage to show me his leg, and I quickly say that it is not necessary.

He goes on to say that he thinks the disarmament is good, and that he does not want to take revenge on those people.

In the women’s ward, we speak to a girl sat on the step of the ward. “I do not know why the Government soldiers started shooting; they had already collected guns a few days before. This was the second time the soldiers came,” she

says.

An older lady joins the conversation. “The soldiers first collect all the people and tell them to sit down. It is those people which try to run away that are shot. She must have panicked and followed them,” she tells me.

The UN Human Rights Watch (HRW) has documented numerous Human Rights Violations by Uganda’s National Army. In January 2007 UPDF soldiers shot and killed 10 individuals, including three children, as they attempted to flee during cordon and search operations in Kaabong district.

MP for Moroto District

Luckily, just before we left Karamojaland the MP for Moroto District was paying Daniel a visit, so we ask him how the Disarmament was going.

Firstly, he explains that he is at the mercy of the Government in the capital, Kampala. Then, he tells us that he is here to organise a series of meetings with the elders from the South, Middle and North in order to join them together and tell their people to cooperate with the disarmament process.

“Tomorrow, they will be travelling north to Kotido, and I will be accompanying them,” he says.

The next morning, we watched the truck leave with the politician and about 20 elders.

“They look scared. Maybe they are afraid the raiders will attack them on the way,” says Mr. Lokai.

Basil says the main problem is that most cattle raiders are young people, and they do not respect the elders anymore.

Back in Kampala

Back in Kampala, I see the Karamojong I got to know in a different light. I have seen what they are escaping from, and how living in squalid conditions in the city is still, somehow, better than being back at home.

Kampala, with its rich walking the streets, must give the Karamojong some sense of hope, and, of course, enough spare change for them to survive.

Out of the individuals we spoke to in Karamojaland about why people are fleeing to the city, most said it was because of hunger. Some even said that they are used to the conflict situation because it has existed for so long.

Future of the Karamojong

No tourism exists in Karamojaland, but great potential is there if the Disarmament can be successful.

It has been proven that modernisation does not mean that traditional culture has to disappear completely. The Maasai warriors of Tanzania, the cousins of the Karamojong, are a good example. They live in relative peace, welcoming tourists to their villages and, usually, having a range of crafts on sale. I have even seen the Maasai in Kampala, sporting their blazing red blankets, sandals and brief cases.

Finally, if our Queen does see any Karamojong on the streets of Kampala during her stay, it will be a huge recognition for all street people around the world. But, sadly, I fear Mr. Museveni will be sweeping the streets clean to give the best impression he can for CHOGM.

So, unlike the rest of us who see the real situation on the street, those VIP Commonwealth Heads of Government, including, of course, the Queen, herself – the people which really have influence – will always be doctored and manipulated for the benefit of the rich, and not the poor.

Thanks to

Simon Lokai https://www.facebook.com/simon.lokaimoe

Bazil Muya https://www.facebook.com/bazil.muya

who acted as translators and helped to collect and edit this information in 2007.

This report was the beginning of a four year stint in Uganda, which ended with an animated documentary about child trafficking of the Karamajong.

Watch the full length film here:

Also find this film on my Vimeo channel: Karamoja City Warriors